Alter, Karen J, and Sophie Meunier-Aitsahalia. 1994. “Judicial Politics in the European Community: European Integration and the Pathbreaking Cassis de Dijon Decision.” Comparative Political Studies 26 (4): 535–61.

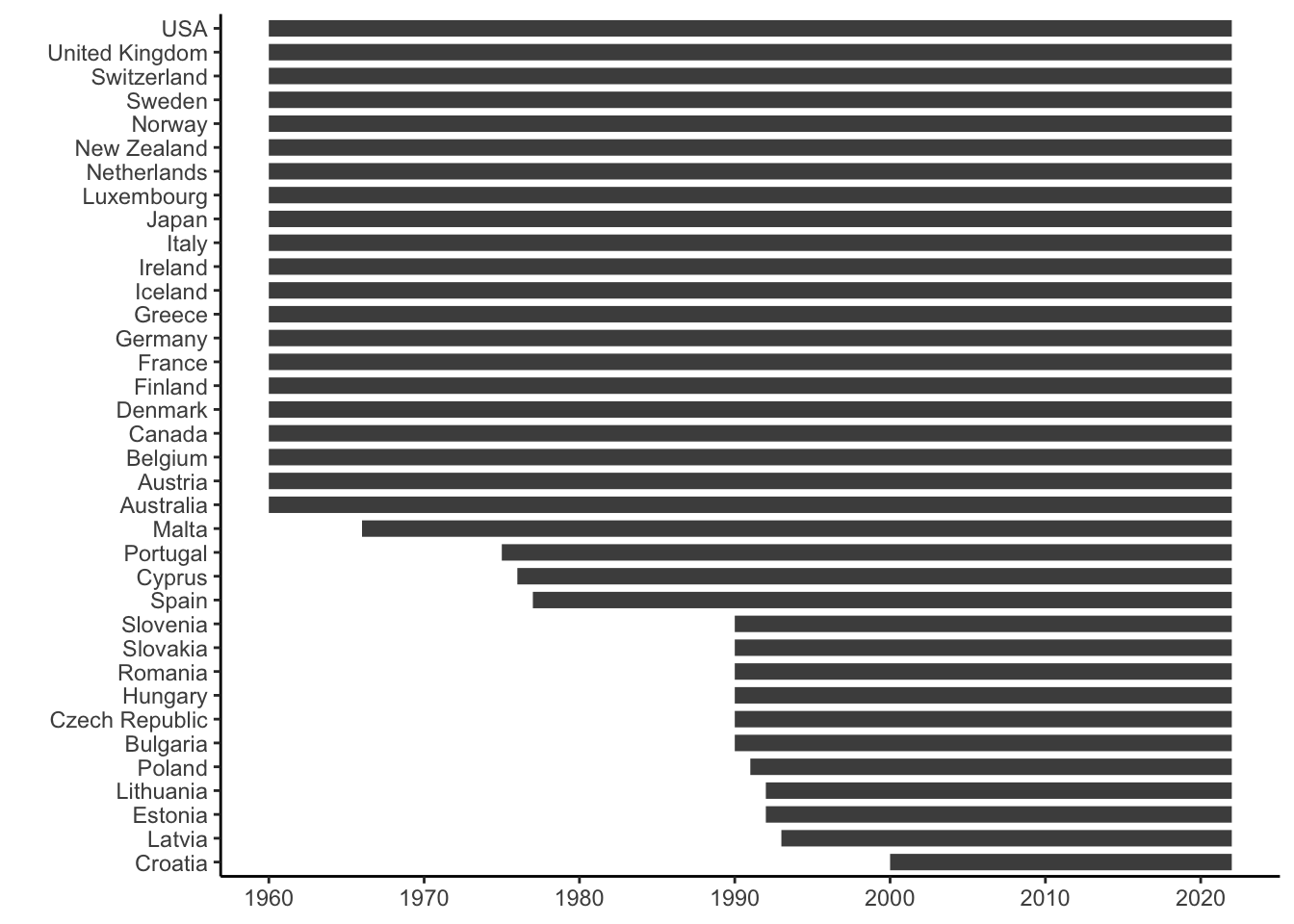

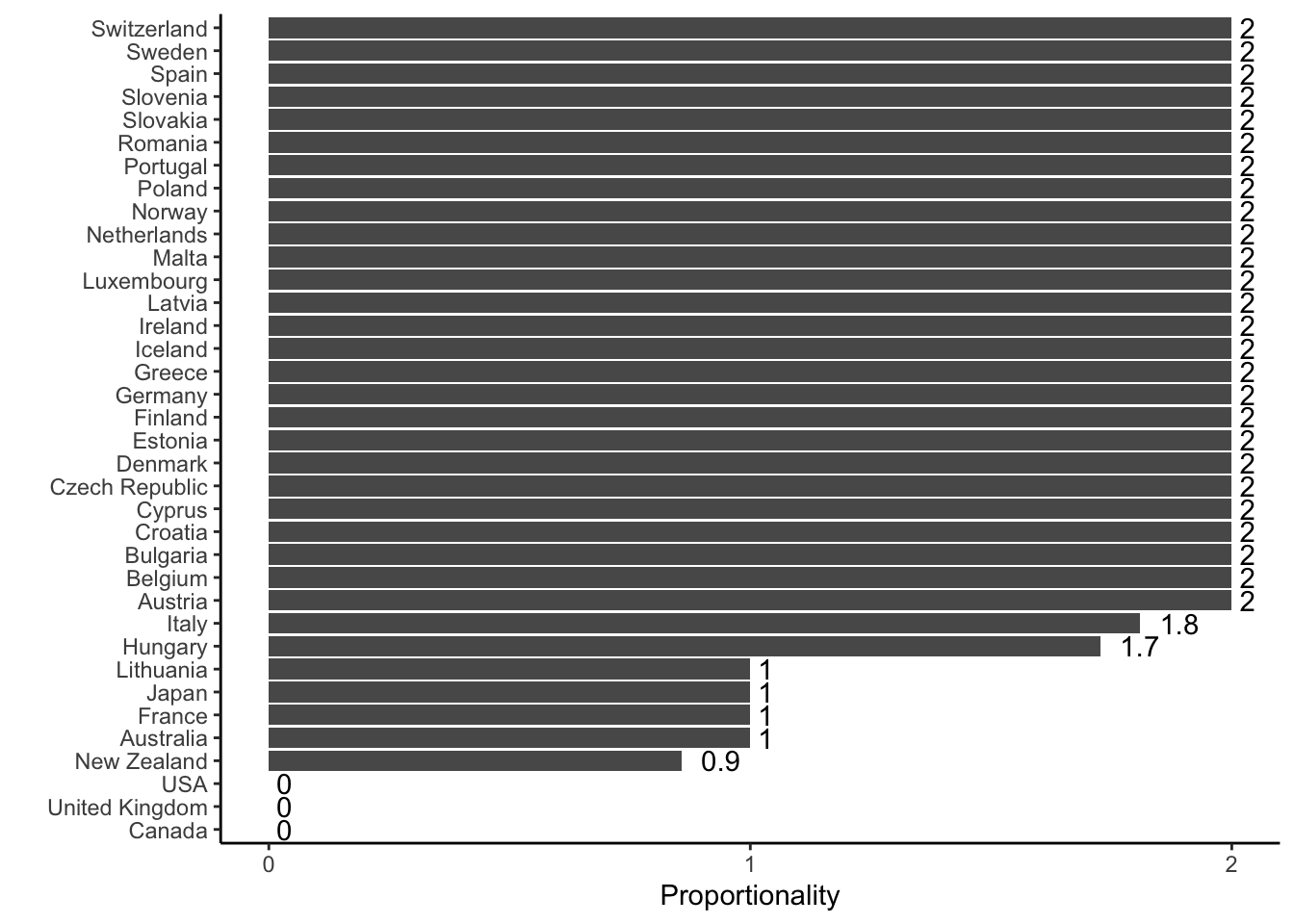

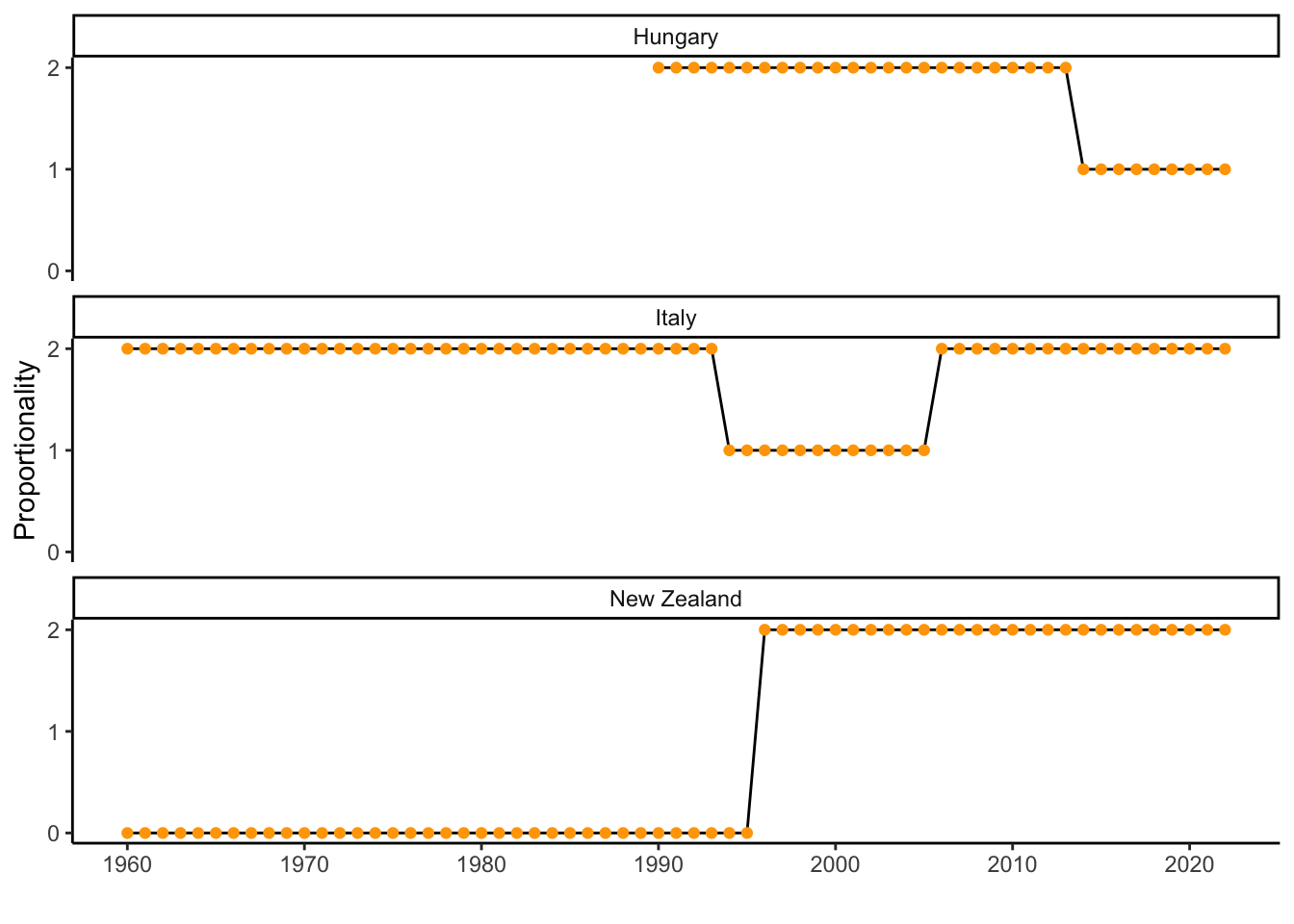

Armingeon, Klaus, Sarah Engler, Lucas Leemann, and David Weisstanner. 2024. Comparative Political Data Set 1960-2022. Zurich, Lueneburg, & Lucerne: University of Zurich, Leuphana University Lueneburg,; University of Lucerne.

Castles, Francis G., ed. 1993. Families of Nations: Patterns of Public Policy in Western Democracies. Aldershot: Dartmouth Publishing Co.

Esping-Andersen, Gøsta. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Fearon, James D., and David D. Laitin. 2003. “Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War.” American Political Science Review 97 (1): 75–90.

Geddes, Barbara. 1990. “How the Cases You Choose Affect the Answers You Get: Selection Bias in Comparative Politics.” Political Analysis 2 (1): 131–50.

Gerring, John. 2004. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good For?” American Political Science Review 98 (2): 341–54.

Golden, Miriam. 2005. “Single Country Studies: What Can We Learn?” Italian Politics & Society 60: 5–8.

Huber, Evelyne, Charles Ragin, and John D. Stephens. 1993. “Social Democracy, Christian Democracy, Constitutional Structure, and the Welfare State.” American Journal of Sociology 99 (3): 711–49.

King, Gary, Robert O. Keohane, and Sidney Verba. 1994. Designing Social Inquiry. Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lindstrom, Nicole. 2010. “Service Liberalization in the Enlarged EU: A Race to the Bottom or the Emergence of Transnational Political Conflict?” Journal of Common Market Studies 48 (5): 1307–27.

Picot, Georg. 2009. “Party Competition and Reforms of Unemployment Benefits in Germany: How a Small Change in Electoral Demand Can Make a Big Difference.” German Politics 18 (2): 155–79.

Przeworski, Adam, and Henry Teune. 1970. The Logic of Comparative Social Inquiry. New York: Wiley.

Ringdal, Kristen. 2018. Enhet Og Mangfold: Samfunnsvitenskapelig Forskning Og Kvantitativ Metode. 4. ed. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

Ruane, Joseph, and Jennifer Todd. 1996. The Dynamics of Conflict in Northern Ireland: Power, Conflict and Emancipation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Seawright, Jason, and John Gerring. 2008. “Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research.” Political Research Quarterly 61 (2): 294–308.

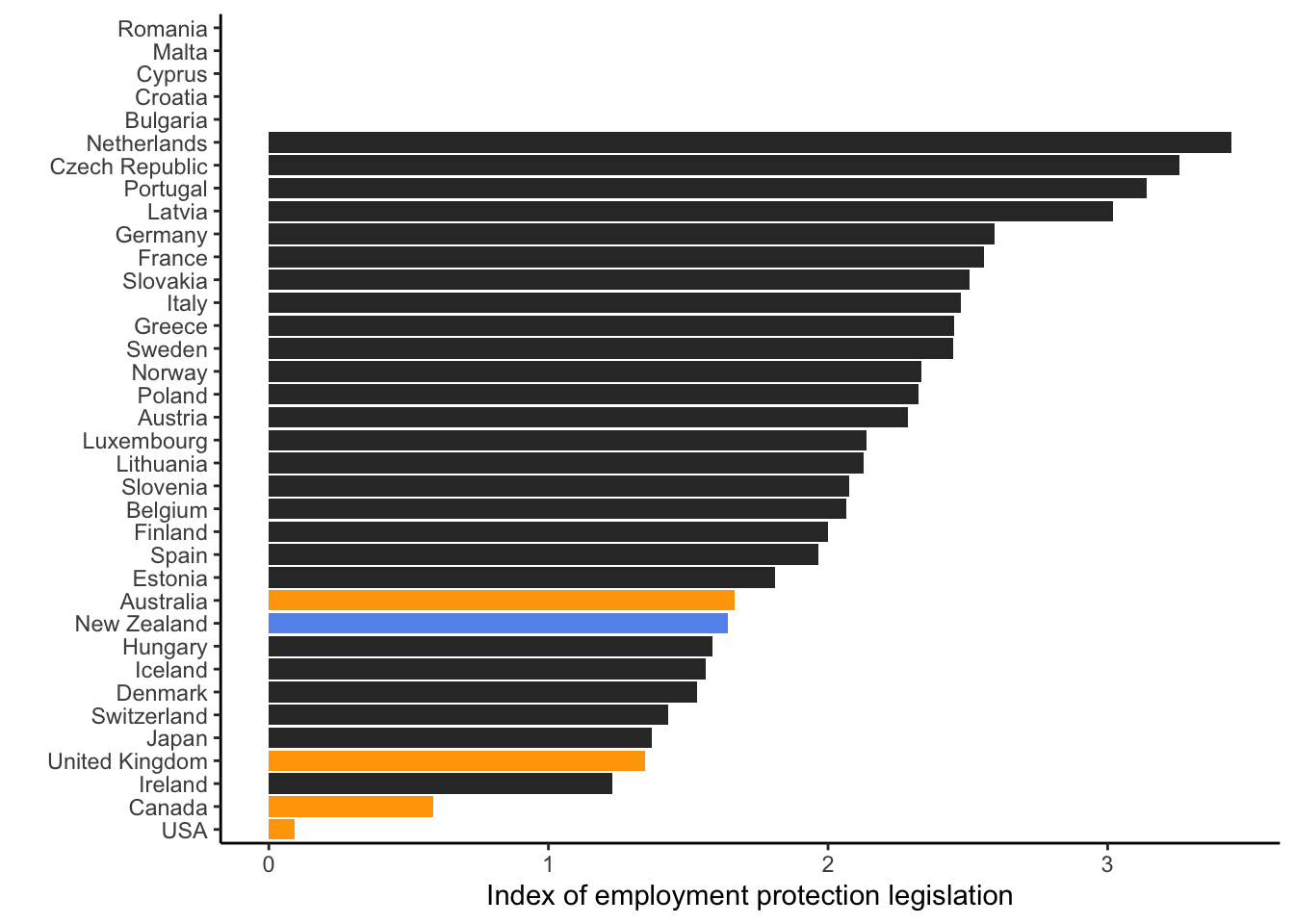

Venn, Danielle. 2009. “Legislation, Collective Bargaining and Enforcement: Updating the OECD Employment Protection Indicators.” OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers 89.