library(tidyverse)

library(bst290)Tutorial 5: Confidence intervals

1 Introduction

You have now made it through the software- and code-heavy parts of the course and learned the basics of data handling and visualization with R. Now, beginning with this tutorial, the focus will shift away from software and code and instead focus more on statistics. This means that the tutorials will say less about how to write code and more about how you make sense of your results.

The reason for this is the following: Running statistical tests and estimations in R is not really difficult as far as coding is concerned. As you will see, most statistical estimations require only a few brief lines of code. The tricky thing is knowing how to write the necessary bits of code correctly. But the most difficult part is how to make sense of the results. Here you need to understand what the different statistical concepts such as p-values or standard errors are and how you identify them in the output that R gives you. And this is why we focus mostly on the latter part, the interpretation.

This being said, we will still use these tutorials to repeat and practice the data management and visualization skills that you learned previously.

We start in this tutorial with the first building block of inferential statistics: confidence intervals. You will learn how to use R to calculate a confidence interval for a sample mean and how to interpret the result — as was explained in Solbakken (2019, chap. 5; see also Kellstedt and Whitten 2018, chap. 7).

As before, we start by working with the small ess practice dataset included in the bst290 package. You will then apply what you learned on real ESS data in the in-class exercises.

2 Setup

R has many statistical tests already built in, so you do not have to install and load specific packages for confidence intervals. But you will need to load the two packages that we have been using in the previous tutorials, the tidyverse and bst290.

And, of course, you also need to load the ess dataset:

data(ess)3 Data preparation

The ess dataset includes a variable that measures how satisfied people are with their life in general, and which is called stflife. This is the variable we will be working with.

You probably remember that you have seen this variable in a previous tutorial, the one one data cleaning and management. Just to refresh your memory: The variable contains responses to the following question: “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole nowadays?”. The respondents could answer on a scale from 0 (“Extremely dissatisifed”) to 10 (“Extremely satisfied”). With a 0-10 scale, the variable qualifies as numeric or linear — and this is good because this means that calculating the mean of that variable and a confidence interval for the mean makes sense!

But: Perhaps you also remember that, although this variable qualifies as a numeric variable, it is stored as a factor in the dataset: You can confirm this using the class() function:

class(ess$stflife)

## [1] "factor"That means we first need to transform the variable to a numeric one before we can proceed.

Technically, this is not difficult. We just use as.numeric() and store the result as a new variable, stflife_num — but we need to make sure to subtract 1 to account for the divergence between the text labels and the underlying numeric values of the variable (see Tutorial 3, section 8.3.1 for details):

ess$stflife_num <- as.numeric(ess$stflife) - 14 Graphical analysis

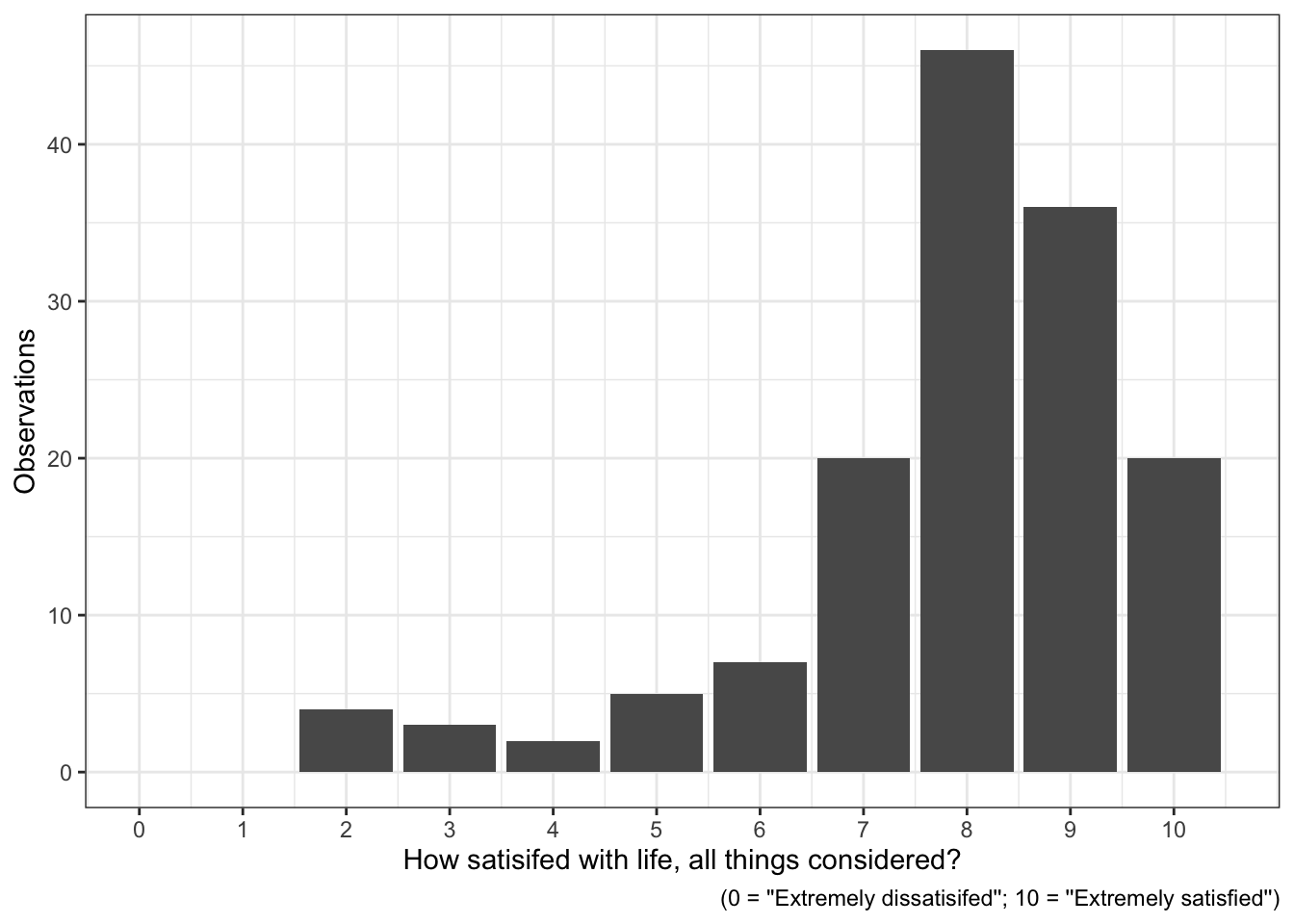

Before we get to the confidence interval, let’s also quickly look at the variable graphically with a bar graph:

ess %>%

ggplot(aes(x = stflife_num)) +

geom_bar() +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = seq(from = 0, to = 10, by = 1),

limits = c(0,10.5)) +

labs(x = "How satisifed with life, all things considered?",

y = "Observations",

caption = "(0 = ''Extremely dissatisifed''; 10 = ''Extremely satisfied'')") +

theme_bw()(We could have also created a histogram with geom_histogram() and set the number of bins to 10 to get a similar result.)

Overall, most respondents are fairly satisfied with their lives. This makes sense: The data are from Norway, and Norway is one of the countries in which people are most satisified with their lives (similar to Denmark, Sweden, Iceland, or Finland).1

5 Getting a confidence interval

We have a variable to work with — now to the interesting part: Confidence intervals.

5.1 Calculating the sample mean

Step 1 is to calculate the mean of the new stflife_num variable — after all, we want to have a confidence interval for the sample mean, which means we have to first figure out what that sample mean is!

Calculating the sample mean is, of course, easy:

mean(ess$stflife_num)

## [1] 7.86014The high value of almost 8 on the 0-10 scale again reflects the overall high level of life satisfaction in Norway.

5.2 Estimating the confidence interval using a built-in function

To calculate a confidence interval for a sample mean in R, you use the t.test() function. This may seem confusing: Why is that function not called conf.int() or similar?

The reason behind this is that the t-test (which you will learn about shortly) and the confidence interval are related (see also Solbakken 2019, chap. 5), and R uses the t.test() function for both procedures. Simply put, the t.test() function relies on the t-distribution, which basically makes an adjustment for the sample size you actually have.

5.2.1 Using t.test()

The code to calculate the confidence interval with t.test() is simple:

t.test(x = ess$stflife_num)

##

## One Sample t-test

##

## data: ess$stflife_num

## t = 52.383, df = 142, p-value < 2.2e-16

## alternative hypothesis: true mean is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 7.563515 8.156765

## sample estimates:

## mean of x

## 7.86014All you do is call the t.test() function and, within it, name the variable for which you want a confidence interval — similar to the mean() or sd() functions! The t.test() function uses the 95% level of confidence by default, but you can adjust this as you will see a bit further below.

The important part of the output is of course the line below the one saying 95 percent confidence interval: Here you see the lower and upper limit of the 95% confidence interval: 7.564 and 8.157.

Can you interpret the result here (see Solbakken 2019, chap. 5)?

You also see the sample mean of 7.86014 mentioned again at the bottom of the output.

5.2.2 Adjusting the level of confidence

It is easy to get a different level of confidence: You just change the level with the conf.level option (“argument”). For example, to get a 90% confidence interval, you run:

t.test(x = ess$stflife_num, conf.level = 0.90)

##

## One Sample t-test

##

## data: ess$stflife_num

## t = 52.383, df = 142, p-value < 2.2e-16

## alternative hypothesis: true mean is not equal to 0

## 90 percent confidence interval:

## 7.611705 8.108574

## sample estimates:

## mean of x

## 7.86014And to get a 99% confidence interval, you run:

t.test(x = ess$stflife_num, conf.level = 0.99)

##

## One Sample t-test

##

## data: ess$stflife_num

## t = 52.383, df = 142, p-value < 2.2e-16

## alternative hypothesis: true mean is not equal to 0

## 99 percent confidence interval:

## 7.468369 8.251910

## sample estimates:

## mean of x

## 7.86014And that is it! You now know how to calculate a confidence interval for a sample mean in R. You may have noticed that we spent quite a bit of time on data cleaning at the beginning while the “meat part” — the actual estimation – was short. This reflects the central aspect of data analysis in R: The easy things are difficult, but the difficult things are easy.

6 Conclusion

You now know how to use R to calculate a confidence interval for a sample mean. As before, there are de-bugging exercises that you can do to practice a bit more. You find these under Tutorials (“De-bugging exercises: Confidence intervals”).

7 (Voluntary) Calculating a confidence interval “by hand”

You probably remember from Solbakken (2019, chap. 5.7; see also Kellstedt and Whitten 2018, chap. 7) that you can also use a fairly simple formula to calculate confidence intervals by hand. And since R can be used as a pocket calculator, you can calculate the confidence interval for a sample mean step-by-step using R.

7.1 The math

The formula to get the 95% confidence interval for the sample mean of a variable \(Y\) is the following: \[CI_{\bar{Y}} = \bar{Y} \pm 1.96 \times \sigma_{\bar{Y}}\]

where \(\bar{Y}\) is the sample mean of the variable, \(\sigma_{\bar{Y}}\) is the standard error of that mean, and 1.96 (no, not 2!) is the critical value for a 95% confidence level.

The standard error of the mean \(\sigma_{\bar{Y}}\) is calculated as follows: \[\sigma_{\bar{Y}} = \frac{s_Y}{\sqrt{n}}\]

where \(s_Y\) is the sample standard deviation of the \(Y\) variable, and \(n\) is the sample size.

7.2 The calculation in R

As before, step 1 is get the mean with the mean() function. Important: We need to store the result so we can use it in our later calculations:

Y_bar <- mean(ess$stflife_num, na.rm = T)

Y_bar

## [1] 7.86014Now we have to calculate the standard error of this mean value. For that, we first need the standard deviation, which we also store:

Y_sd <- sd(ess$stflife_num, na.rm = T)

Y_sd

## [1] 1.794363And then we need the sample size. Here we need to pay attention that we do not accidentally count missing observations (NAs). We do this by letting R calculate the sum of non-missing (!is.na()) observations of our variable:

Y_n <- sum(!is.na(ess$stflife_num))

Y_n

## [1] 143We can then use the sample size and the standard deviation to calculate the standard error:

Y_se <- (Y_sd/sqrt(Y_n))

Y_se

## [1] 0.1500522Now we have everything we need. All we have to do is to plug the values into the main formula. First, we calculate the upper limit of the confidence interval and store the result:

upper <- Y_bar + 1.96 * Y_seThen we calculate the lower limit while storing the result:

lower <- Y_bar - 1.96 * Y_seAnd then we print out the result:

lower

## [1] 7.566038

upper

## [1] 8.154242If you pay close attention, you may notice that the interval we get here is almost identical to the one we got when we used the t.test() function.